By Ananya Mukherjee

“Excuse me, yeh Begumpet kitna door hai?” I asked, rolling the car window to a man at the first traffic signal. It was my first day, my first tryst on the roads of one of India’s most modern metropolis, Hyderabad.

“Excuse me, yeh Begumpet kitna door hai?” I asked, rolling the car window to a man at the first traffic signal. It was my first day, my first tryst on the roads of one of India’s most modern metropolis, Hyderabad.

“Excuse me, yeh Begumpet kitna door hai?” I asked, rolling the car window to a man at the first traffic signal. It was my first day, my first tryst on the roads of one of India’s most modern metropolis, Hyderabad.

“Excuse me, yeh Begumpet kitna door hai?” I asked, rolling the car window to a man at the first traffic signal. It was my first day, my first tryst on the roads of one of India’s most modern metropolis, Hyderabad.

The man I threw the question at was in a sparkling white polyester half sleeve shirt and white lungi and reminded me instantly of a detergent commercial. He was sitting astride on a bike that had more bling than steel and as he spit a spray of red betel juice flashing a stark white set of dentures, I was convinced that I was caught in a commercial gone wrong, terribly wrong. Against the dark tone of his skin, the pearly white smile with crimson red betel juice stain was highlighted as if in bright neons.

“Amma,” he started to speak and I froze! Amma, who me? Heck, I was in my mid-20s, smartly dressed, hired as a Lifestyle journalist by one of the most popular English dailies in Southern India, and a man old enough to be my dad was calling me Amma?? It hurt my pride, most importantly my fashionable alter ego!! Anyway, little did I know then that the local culture was not particularly influenced by Oedipus complex or leaning on any incestuous dogma; in fact, addressing a woman as "Amma" was considered a sheer display of affection and respect and accepted gracefully by anyone in skirts bereft of their seniority in rank or age. I, however, developed that insight only after I had spent a couple of months in the city.

Refocussing my thought on the road, I stared at him with the same question in my eyes. I was running late for a meeting. Amma or Behenji, I needed to find my way to Begumpet, and I needed him to oblige fast.

“Left ko katke, right ko marne ka. Phir sidhha ekich road” my detergent man declared in what I assumed to be a “warlike hostility” and zoomed away.

It was only when the car trailing mine started honking rather rudely that I realized that I was still standing at the road signal, racking my non-violent brain to interpret whatever that meant…”left ko katke, right ko marne ka”…ouch, Was I in the battlegrounds of Haldighati or Hyderabad? Whatever it was, the "marna-katna" made me feel like a princess in an armour that needed some greasing!

And so began my tenure in the city of Nizams and IT geeks!

Hyderabad was my first address in Southern India in 25 years since my birth. Born in Jammu, raised partially in Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, Maharashtra, Punjab, Orissa and Madhya Pradesh, like most Bengalis from Lake Market (my ancestral home in Calcutta) I too was brought up with a veiled assumption that anything beyond the Deccan was simply “Madraasi”, that all " Madraasis" ate sambhar, idly and dosa three times a day, wore Kanjeevaram sarees and listened to Carnatic music. That Telugu, Tamil, Malayalam and Kannada had very distinct identities, the states, the culture, the food and their people clearly different from each other, was a learning I gathered only through the experience of living and spending time in each of them.

I remember one incident in particular, very vividly. I had just moved into a new penthouse apartment in an upmarket locality and used to be woken up at the crack of dawn every morning with the loud singsong hawking of a street vegetable seller. I would not credit it to be the most pleasant of wake up calls, especially since this echoing shout was in a language I did not understand at all. Each morning, come rain or shine through the monsoon swept by lanes of the neighbourhood, he would go stressing his vocal chords on something that sounded like Aiaaaashwarrrrya…….. I quickly linked it to the established perceptions in my mind. Wow, that was a steal…they sold Aishwarya in wicker baskets on the streets of Hyderabad, I thought! Now how would the former Ms World and Bollywood’s First Bahu react to that is a story we shall discuss another day!

I could not of course hold my curiosity for too long. One morning I dragged myself out of bed to check the Aishwarya that was so generously being sold outside my apartment gate. To my chagrin, it turned out to be a cartload of green leafy vegetables! So disappointed I was with my discovery that I never bothered to check what the correct pronunciation was.

In hindsight I think, there was something almost planetary about my connection with vegetables in Hyderabad. On another occasion, while I was rushing home from work on a very busy day, passing through a rather congested fresh vegetable market, I almost choked in repulsion as I heard the vendor ceremoniously screaming in a hoarse stereophonic voice…PEDDA PEDDA PADI PADI. In his hands were two huge cauliflowers. Needlessly to say, my flabbergasted mind instantly connected his outcry to the vegetable and my nose twitched. I could almost smell the imaginary stench! Of course, I soon discovered much to my amusement that “pedda” innocently meant large and “padi” was not obnoxious in the least: it meant the number 10. The fabricated horror was only a figment of my own limitations! The poor man was only selling large sized cauliflowers at Rs10

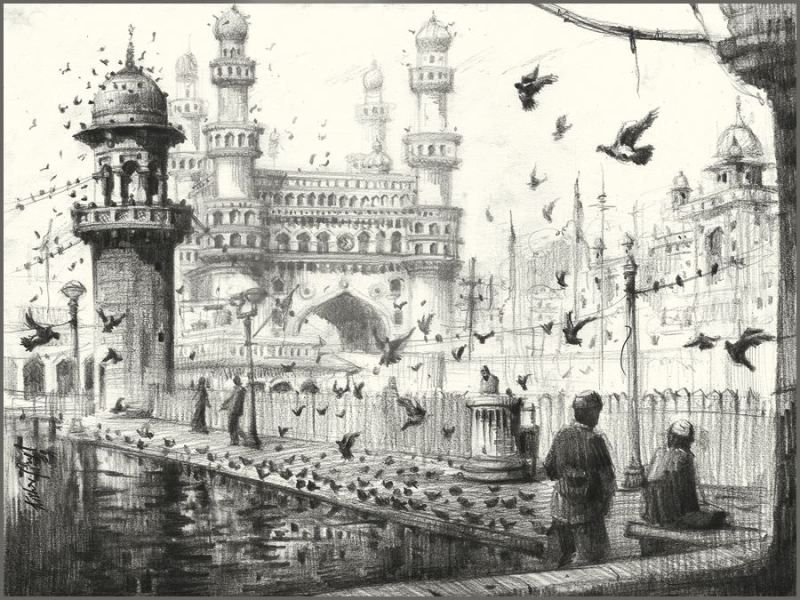

Hyderabad, to me, had its own charms; it was an amazing blend of what the Nizams left behind and what the IT boom did to it. Amidst the biryani from Paradise, the Kanjeevaram draped, coconut oiled and jasmine haired women, the turmeric smeared feet, the IT and SFO connections, where nearly every house had a son living in the US of A, the potted tulsi plants and rangolis, the old world charm of Golconda Fort, Salar Jung Museum, the Charminar, the narrow by lanes around it that sold silks, Kalamkari and Bidri art, lac bangles, pearls and Haleem, there was a bustling metropolitan, where women drove home safe at two in the morning, the tap water “manjeera” was ready to drink, the queues moved faster than most other cities and no one complained of eve-teasing, rape or sexual harassment at work.

Also, I can’t do justice to Hyderabad, if I don’t talk about the Hyderabadi Hindi. My first rendezvous on the road on the very first day was just a curtain raiser. But talking about Hyderabadi Hindi, it is bound to connect you to the memories of our erstwhile Bollywood comedian Mahmud. It is so uniquely coarse, delightfully tangy and surprisingly sweet at the same time that I developed an intense ear for it and picked up conversations from wherever they happened. On one such incident of eavesdropping, I heard someone say "Visa Balaji." My ears had not been particularly efficient in picking the right pronunciations, so I made no assumption this time and queried, “what?”

“Tumko nai maloom, amma?” By now I was used to being called Amma. So long as no one called me Behenji, it seemed acceptable. My maid Saroja, took great delight in enriching my knowledge by answering my quest. “Visa balaji sabka visa karta.” I thought she was talking about a travel agent, Balaji and Venkat were undoubtedly the two most common names for all shops and men that I knew of in Hyderabad. “Balaji kaun? Agency?” I probed.

“Nahin amma, Balaji bagwaan.” And she touched her forehead. “Tirupati balaji bagwaan, tum janta na?”

Yes, I knew her “Balaji bagwaan” but had not met him in person, I joked. Saroja seemed not bothered by my insolent humour. Instead she suggested, “Tum jao Balaji ko bolo. Tumhara bhi visa ho jayega. Idhar kayekoo raheta? Sab phoren jata. Tum bhi jao.”

I can’t say whether it was on her insistence or my own relocation plans somewhere in the back of my mind, that I took Saroja’s suggestion seriously and decided to pay a visit to the pilgrimage in Chilkur, a small village at about an hour’s drive from Hyderabad. The folklore around it went thus: One particular devotee of the Lord Narayan or Balaji was too old/feeble to go pay a visit to the Lord in his temple. But the devotee’s yearnings were so sincere and intense that Balaji made an appearance in his own modest hut to bless him. The hut was now transformed into a temple.

What I saw there left me enthralled: men, women, children, denim clad teenagers with branded coolers, the ready to hop on to the next flight to Silicon Valley kind young adults, the devotees came in thousands each day, perambulating the inner circle of the shrine, praying and pledging to offer gifts and donations, should Balaji once listen to their prayers and ensured that the passports got the respective desired visa stamps.

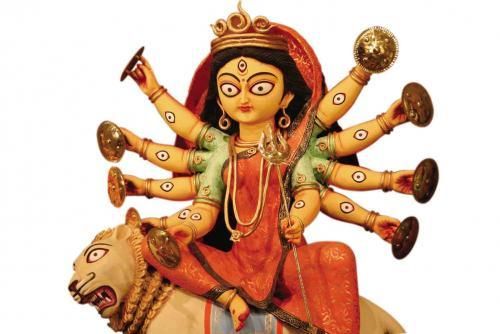

There was something so spectacular about the temple, the faith that drove these hundreds of thousands of believers and I started visiting it again and again. Not for a visa, not even for a wish to be granted but to be a part of the whole spiritual experience of submission and faith in the power of the divine.

On one such morning at the start of the Bengali New Year, I decided to visit Chilkur again. Unfortunately, luck was not on my side that morning. I missed the alarm, woke up late and struggled to get out of the morning traffic of Hyderabad. Once I was out, I missed the exit and had to drive another 20 kms before I reached the first U-turn. By the time I reached Chilkur, it was almost midday, hot, sultry and the summer sun was harsh on the skin. The temple as usual was crowded with devotees streaming in from luxury coaches, station wagons from far off villages, cars and tempos. I must have been behind 2000 people in the snaking queue that moved at a snail’s pace. It was only after a couple of hours of waiting when I entered the inner shrine from the outer premise of the temple, that I started hoping to catch a glimpse of the deity. Little did I know that the door was soon to be shut for the “Bhog” or lunch recess. Almost an inch away from the main altar, just as I was about to step in, the head priest raised his hand and stopped the queue from moving. It was time for Bhog he announced. The temple would only open after Balaji had rested well. By then, I was leading the queue. I don’t know if the frustration showed on my face or it was something else, he called out to me in fluent English, “You, come here. Help me clean the flowers from the floor and the inner shrine. “

With that, before I knew it, he handed me a basket and took one himself, and we collected the marigolds and roses strewn on the altar at the feet of the Lord. Finally when it was done, the priest signalled for me to step into the inner shrine where the Lord was seated. “No rush, you can pray.” He said gently placing a silver crown on my head in blessing. I stood there, transfixed, unable to comprehend the significance of the whole situation. All I now remember is that I mumbled something about being grateful, and asking for strength, endurance and courage to be myself.

What followed next was rather an interesting fact. I don’t know if it was the blessing of the much revered “Visa Balaji Bagwaan” or just some divine coincidence, I found myself relocating to Singapore for good in just six months' time.

It was nearly a decade ago. I have not visited Hyderabad since, but when I look back, I feel a gush of warmth, of acceptance, of familiarity laced with the smell of coconut milk and curry leaves. The streets may not have sold beautiful women in wicker baskets as I had imagined at first, but they bartered beautiful memories for a pause to last a lifetime...

This article was first published in my regular column Sudhh Shakahari Desi in Bkhush.com