Sunday, November 29, 2015

Saturday, November 28, 2015

Patiala Peg

By Ananya Mukherjee

Singapore

Backdrop: A freezing winter night in Patiala in the year 2001.

Singapore

Backdrop: A freezing winter night in Patiala in the year 2001.

It was half past midnight when I

heard the doorbell ring. As planned, I wrapped up my little girl in a thick

woolen blanket. She was fast asleep in her long johns. Picking her as quietly

as I could, I tip toed to open the hard wooden door. A sharp cold breeze

whisked past me through the second layer of the net door. In the mist-filled dim

greyish blue light of the staircase, I could only see the shadow of a man.

Well-built to the extent to be

called athletic, he was covered in heavy woolen clothes, that included a cap

drawn over his head covering most of his face. His neck was wrapped in a thick

muffler. A dark leather jacket rose up to this throat.

The chilling wind was making it

difficult for me to stand steady. He asked me if I were ready. I nodded my head

and handed over my child to him. Then I

went in to bring my own red leather coat, cap, and gloves. With my hands

trembling at the winter cold, I managed to lock the main door as noiselessly as

possible and went down the staircase following him.

We paced up the drive way without

exchanging a single word. When we had

nearly reached the gate, he turned back once as if he had changed his mind. My

eyes perhaps had a questioning look for he handed over my girl back to my arms

and said, “I don’t want any noise. Leave the iron-gate. Let’s jump over the

boundary wall. Wait, I will jump first. You pass her over. Then you jump

across. “

I did as I was told. He crossed

the boundary wall to the other side and waited. I passed my daughter over and

jumped across. It was cold as cold it could get and we were freezing in the

open lawn. We waited for a few seconds before he picked up my daughter from my

arms again and went inside a dark bungalow. He came out after a few minutes and

locked the doors of the house where he had just left my little girl. We hopped

into his car as silently as we could and just as we were about to leave, I saw

a man standing in a balcony watching us from across the road. His gaping mouth

had the most incredibly horrified expression as we drove away, laughing.

Yes, you read it right. Laughing

till we choked! We had just created the spiciest gossip in the neighbourhood! If

you are wondering what this is all about, let me explain.

That man who I supposedly “eloped

with in the wee hours of a winter night” was Colonel Bhatta, my husband’s

friend and colleague in the Indian Army. We had been neighbours for almost a

year. When two Bongs are thrown into a place far away from home and end up

living next doors, they no longer remain friends. Between couriers of aloo posto and maacher jhol, shukto, khichudi and kosha mangsho across boundary walls and evenings spent in Rabindra sangeet, adhunik gaan and all

things Bong, they become one large family. So it was with us. Col Bhatta and

his beautiful wife Shikha soon became a part of our extended family in Patiala,

where my husband was pursuing a MD in Sports medicine. Needless to say, most of

our memories are of moments we spent in the company of the Bhatta’s. In

hindsight, I can barely remember an evening we had dined separate in our

individual homes. Typically, our days as

young mothers would be busy housekeeping and running around the kids. My

daughter was particularly close to the Bhattas and picked up many of life’s

first lessons in the company of our kind hearted neighbours. On a usual day, as

soon as the men came back in the evenings, we would gather together, bring in some

food either in their lawn or on our terrace, light up a camp fire and have a

drink and dinner like one big family. There were days when the fog and the

chill would get so strong, we would all slip inside huge quilts in a well

heated room and chat the night through.

It was on one of those winter

nights when my husband was away, and we were having dinner together when Col

Bhatta asked me how Doc was returning. I told him that my husband who was

travelling by train had to disembark in Ambala Cantt ( since Patiala had no

railway station) and would most likely rent a cab home. An idea was proposed that post dinner, all

five of us, including Gungun who was two

and Shubhang (their son) who was nine would join the reception troop to bring

home Doc. It was meant to be a surprise. It also meant we needed to drive 40

kms in the early hours of the morning in the cold to reach Ambala Cantt

station.

Unfortunately, later in the

evening, the children fell asleep too early and Shikha’s migraine surfaced from

nowhere. So our plans had to be altered. Shikha proposed I leave Gungun with

her and go ahead with Col Bhatta to receive my husband.

So that’s the real story, and

that’s exactly what we did. However, to the spying, perceptive eye coated with

conviction, it seemed like a perfect neighbourhood gossip. The incident remains

etched as one of my fondest memories of the princely state of Patiala till date.

For those of you, who associate

the name of the city with the measure of liquor equivalent to 120 ml, or the

extravagant Patiala Peg, here’s a story we learnt during our stay.

One of our banker friends in the

Civilian community outside of the Army territory would often invite us to the

Maharani Club. Located in the midst of Baradari garden in the very heart of the

6-km radius town, the majestic red tile-roofed mansion was said to resemble the

pavilion of the Oval England. The architecture was a blend of the colonial

influence and the royal grandeur of the erstwhile state of Patiala. Interestingly,

Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala was the captain of the first cricket team

that visited Britain way back in 1911. He also had an indomitable Polo

team. Before its civilized version or

Tent Pegging, the army was known to play skull pegging where an army of fierce

warriors would ride on their horseback, pegging skulls of their enemies’ buried half in the ground, along the way. With time, the game changed its format

and friendly matches began to be organized. It was during one such “friendly”

invitation that the Viceroy’s Pride arrived in Patiala for a match. For some

reason, the home team felt threatened and nervous that they would face a loss

and the wrath of the fearsome Maharaja, hatched a conspiracy.

On the evening before the match,

the Viceroy’s Pride was invited for a drink at the Maharani Club where a double

measure or the first Patiala pegs of whiskey was served. Needless to say, the

Maharaja’s team won the match the next morning.

The legend of the Patiala Peg lives on.

Patiala is a treasure trove for

short story lovers. My husband’s school, the National Institute of Sports, was

a part of the sprawling princely palaces and gardens right in the royal

district of the city. Every trip opened up a Pandora’s Box of tales and

folklore. One of the famous ones, as I now recall was about Maharaja Bhupinder

Singh and his fleet of Rolls Royce cars. When the Maharaja visited a Rolls Royce

showroom in Britain and enquired the price of a premium model, he was

humiliated by a salesman who doubted his affordability. The infuriated Maharaja

Bhupinder Singh not only bought all the cars from the showroom, he cut open the

roofs and began to use them as garbage trucks. No sooner did the news reach

England, an apologetic Rolls Royce envoy requested the maharaja to return all

the garbage truck and replaced them with the finest and most premium models.

It was also during our two-year

stay that I picked up other gems; words in Punjabi that I would not have known

by simply watching Bollywood movies or being an Army wife ( where for some

reason people simply assume Punjabi to be the most spoken language after

English in the mess before General Kapoor says so ). A horribly misinterpreted

phone call taught me that “lukhh” had little or nothing to do with

Lukhnow, that the colour of the turban

shared some hints about the clan or identity, that makki da ataa must always be

kneaded with warm water and never rolled; that there was nothing so heavenly as

stopping by a Dhaba on a long drive to sit and relish a freshly baked alu ka

paratha with makkhan di tikki on top and a glass of malaiwali lassi; that it

was perfectly normal to attend weddings with ‘Mandeep weds Mandeep’ written on floral

plaques ( one just needed to ‘see’ the implied Singh and the Kaur), that no one

cared if tandoori kukkad was the national bird or not so long as it found a

spot in the dinner plate, that “naardana” chowk meant “anaardana”; and that a

desperate looking youngster suffering from cardiac arrest like symptoms on a

hot summer afternoon complaining of “book ni lagda, neend ni aandi, jee gabrata

“ at our door could actually be the proud owner of a name such as Aashiq

Ali.

I also learnt a thing or two about the large heartedness and

progressive mindset of the Sikh community. My many trips to Dukhniwaran

Gurudwara, watching the kar sevaks, attending the langar, were the most

humbling experiences of my lifetime.

And I would do little justice to my memories of Punjab if I

do not mention a lady called Leela.

Leela auntie, all of 50 then was my domestic help. Her

mother had come as a part of the dowry with the Maharani of Patiala. Leela

auntie was born in the palace grounds and was raised serving the first family

of Patiala. Before she started working for me, she had spent six years in

Singapore and another four in Hong Kong working as a helper in NRI households.

When she came back, from whatever money she had saved, she invested in her

daughter’s college education and in building a double-storey house for herself

and her family. I would often question her why she needed to work in her age, and

a response would be “ Aurat ko na humesha kaam karni chahiye. Khud ka kamana

chahiye. Tabhi uski izzat raheti hai,” ( A woman should always be financially

independent. Only then can she get the respect).

We left Patiala in 2002 and 13 years later, as I look back

at the memories and reminisce the wonderful times spent in the company of some

warm hearted people with such a positive happy outlook towards life, my eyes

get a wee bit misty. I am not a drinker but I might as well pour myself an

extra helping of my favourite port wine and raise a toast to the Patiala Peg.

Cheers!

Wednesday, November 25, 2015

Intellectual Property

This blog is copyrighted by the author. Any reproduction, reprint or publication in whole or parts thereof in any other form without permission is a violation of the intellectual property right and could lead to potential legal actions by the author.

Friday, November 13, 2015

A bit of a role play

Consultant: "Well, you have the highest scores that I have ever seen in optimism and stress management. Never met a profile such as yours. My own scores are pathetic. How do you manage to achieve this?"

Yours truly: ( smiling ) " Frankly, I do not know what I manage better; disappointments or dreams."

Her eyes begin to sparkle. Or maybe they are reflecting (on) mine. I leave the room smiling at the role play.

Flashback and more

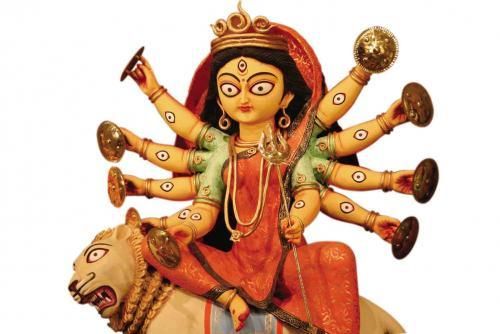

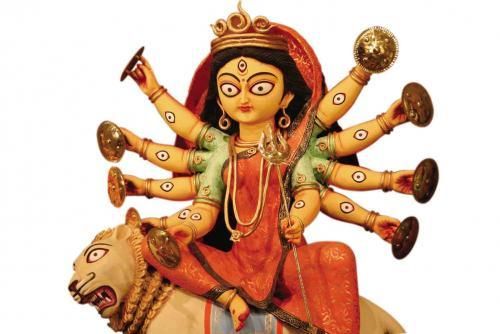

In my ancestral home in North Bengal, this is the busiest time of the year. Folk lore has it that the Khan Bahadur Bhaduris many centuries back descended from a family of dacoits and made their fortune by amassing wealth and land from the kings and landlords. Before every raid, they were known to offer an animal sacrifice to the goddess Kaali. In due course, over a few generations, they became feudal lords themselves, gave up on robbery and adopted the lifestyles of Zamindars. However, the loyalty to the goddess of shakti or Kaali continued and a temple on home grounds was built over an altar of panchmundi or the sacrificed heads of five humans. Even today, the temple stands strong in the courtyard amidst the dilapidated remains of the old mansion and the modern structures where our extended families live.

Kaalipujo continued to be the most awaited festival at home and throughout my growing up years, an annual ritual for the dispersed family to reunite. During my grandmother's time, as the senior most matriarch of the Khan Bahadur Bhaduris, she was the sole controller of the elaborate family run extravaganza. Everyone else merely followed orders.

Interestingly, everyone in the village and in the neighbouring villages were invited. No one who lived within the radius of 5 kms, stayed hungry on these days. Thamma, till her 90s, continued to fast all day and prepare the Bhog for the pujo.

It was during one of those annual visits to home, that she told me a story.

Once in the midst of the festive season when her grand mom in law Bindubashini Debi was preparing the bhog, a little village girl came and stood near the main kitchen. She looked like a peasant's child, matted hair and frail, and someone probably from a lower caste. How she had found access to the zamindari kitchen or the courtyard of a bramhin family was unknown. The girl apparently spread out her hand begging for food. Bindubashini Debi was so engrossed in cooking for the goddess that she snapped at her insolence, explained that it was bhog meant for Ma Kaali, ignored the child and ordered the servants to drive her away. No one eats what's prepared for the gods before it is offered in prayers. Only after the bhog is religiously offered, can the prasad be distributed amongst devotees. The little girl went away forlorn and sad.

That night Bindubashini Debi had a dream where she saw Ma Kaali rebuking her in her sleep and refusing to accept the bhog. " I came to your doorstep asking for food and you drove me away. Now I shall not touch your bhog," the sad Goddess said. Bindubashini Debi must have realised her mistake for she sought forgiveness and declared that the whole village and its neighbourhood be invited for the pujo. A decree was passed that no one within 5 km radius of the zamindari would sleep hungry that night and if anyone ever asked or begged for food even meant to be offered to the gods, it must be given out to the person first.

For generations, we have stuck by the unique code. In all our festivals and prayers, in rituals and celebrations, it is always about practising human first, then God.

Kaalipujo continued to be the most awaited festival at home and throughout my growing up years, an annual ritual for the dispersed family to reunite. During my grandmother's time, as the senior most matriarch of the Khan Bahadur Bhaduris, she was the sole controller of the elaborate family run extravaganza. Everyone else merely followed orders.

Interestingly, everyone in the village and in the neighbouring villages were invited. No one who lived within the radius of 5 kms, stayed hungry on these days. Thamma, till her 90s, continued to fast all day and prepare the Bhog for the pujo.

It was during one of those annual visits to home, that she told me a story.

Once in the midst of the festive season when her grand mom in law Bindubashini Debi was preparing the bhog, a little village girl came and stood near the main kitchen. She looked like a peasant's child, matted hair and frail, and someone probably from a lower caste. How she had found access to the zamindari kitchen or the courtyard of a bramhin family was unknown. The girl apparently spread out her hand begging for food. Bindubashini Debi was so engrossed in cooking for the goddess that she snapped at her insolence, explained that it was bhog meant for Ma Kaali, ignored the child and ordered the servants to drive her away. No one eats what's prepared for the gods before it is offered in prayers. Only after the bhog is religiously offered, can the prasad be distributed amongst devotees. The little girl went away forlorn and sad.

That night Bindubashini Debi had a dream where she saw Ma Kaali rebuking her in her sleep and refusing to accept the bhog. " I came to your doorstep asking for food and you drove me away. Now I shall not touch your bhog," the sad Goddess said. Bindubashini Debi must have realised her mistake for she sought forgiveness and declared that the whole village and its neighbourhood be invited for the pujo. A decree was passed that no one within 5 km radius of the zamindari would sleep hungry that night and if anyone ever asked or begged for food even meant to be offered to the gods, it must be given out to the person first.

For generations, we have stuck by the unique code. In all our festivals and prayers, in rituals and celebrations, it is always about practising human first, then God.

May Ma Kaali, the goddess of Shakti give you strength, courage and power!

The Distance

How far are you from yourself?

Half a breath away.

Always?

No. When I am alone.

And with people around?

A few million light years, sometimes.

Half a breath away.

Always?

No. When I am alone.

And with people around?

A few million light years, sometimes.

Thursday, November 5, 2015

Sing me a song, Ma!

Lullabies or loris. Are they things of the past?

I don't know what lullabies or loris our kids will sing to their next generations, but I still love the ones I grew up listening to in my childhood and sang to Gungun before putting her to sleep every single night when she was a baby. There used to be something so innocently beautiful about the ritual....change into your night suit, brush your teeth and slip inside the quilt. In that dim soft light of the bedroom, my Mamma would hum to me, gently patting all the while, songs, ballads, rhymes....I followed the same ritual with Gungun. She needed her lori, learnt her first songs and poems and even participated in singing them in return to a tired "sooo jaa ab meri maa" me. As I look back, the simple act fills me with a beautiful memory of bonding, of passing a culture and a tradition to the next generation. No?

I don't know what lullabies or loris our kids will sing to their next generations, but I still love the ones I grew up listening to in my childhood and sang to Gungun before putting her to sleep every single night when she was a baby. There used to be something so innocently beautiful about the ritual....change into your night suit, brush your teeth and slip inside the quilt. In that dim soft light of the bedroom, my Mamma would hum to me, gently patting all the while, songs, ballads, rhymes....I followed the same ritual with Gungun. She needed her lori, learnt her first songs and poems and even participated in singing them in return to a tired "sooo jaa ab meri maa" me. As I look back, the simple act fills me with a beautiful memory of bonding, of passing a culture and a tradition to the next generation. No?

Dugga Dugga

It is almost impossible to observe, reflect and then honestly narrate the juicy chronicles of a Barowari Probashi Durga Pujo (the annual Community Bong festival) without rattling a few cages and raising a few well- trimmed eyebrows (they already look arched high enough with the pujo chaant , like an expression of perennial surprise; a couple of millimeter more would hit the roof….oops, the hairline)!! Shhhh.. I was just being polite. I actually meant opening a can of creepy crawly worms. Eeeks…I can see you cringing at that! Trust me, so am I. To be absolutely truthful, and I cross my heart as I say this, that’s a just a simple breakdown of what we, the flag bearers of back stage management and front row audience, call Poro Ninda Poro Chorcha or PNPC in short.

You do not know what PNPC is? You gotta be kidding or you are not qualified to be a Bong! Ok, let me have the exclusive privilege of enlightening you on the fodder that we live on. PNPC is the staple bong diet after the bhoger khichuri for any community Durga Pujo, whether in homeland or on foreign shores. It is a must; like the panchamrita that cleanses your soul post fasting? There you get it! It is the quintessential detox of the Bong mind….just throw up all the snide remarks, nose twitches, lop sided smiles, sarci jokes at one go and there you are the decontaminated pure spirit ready to absorb the blessings of the sacred mantras and indulge in more observation of the clan around you.

For once, even I cannot slip into my self-assumed social anthropologist’s role watching the antics of a known tribe without identifying with it. So let’s get back to the real scene. Did you read “battlefield”? Oh no! We are the “kaalchaared” intellectual genes. PNPC is never done aloud. We do all this very subtly and if you are the probashi Bong, there are chances you would not even get it. It could start with a simple query: “Tumi Kolkatar?” (Are you from Kolkata?) . You are dead, if you dare say “yes” and later reveal an address that’s indicative of a pincode in South 24 Parganas. “Narendrapur abar Kolkata naki? Bollei holo!” ( Since when did Narendrapur become Kolkata! Crap). Well…to the unsuspecting mind, it is just the beginning to a compartmentalization, almost as definite as the MBTI test if you have ever taken one. The next lines of questions are somewhat predictable. Ghoti na Bangaal? North Cal or South? Which school did you say? You are saved again if your school has a reputation to be hip. Even better if you have a convent tag attached to your alumni and can sing the commonest school prayer “Our Father, thou art in heaven….” to perfection. Also, even if you do not drop slangs as punctuation marks in your conversations, you must know what they mean! “JU? No wonder!!” With each question, mind you, you are becoming a part of a quadrant and don’t ask me the axes!

Now that you have been measured (up and down) and somewhat fit into a prototype of a certain creed of Bongs, we will look at your clothes…yes, the saree and goyna cannot find a better exhibition than the puja mandap. Commissioned designer exclusives to Gariahat morer stalls, copies of Sabyasachi and Satya Paul to online carbon prints, displaying your wardrobe over five glorious days is the heart of Bong Durga Pujo. There can be nothing as traumatic as discovering the lady standing beside you at pushanpanjali wearing a saree similar to yours. Did I say traumatic? Read catastrophic! The dokaandaar who promised you “ektai piece didi” is dead and so is dear hubby who spent some few hundred dollars buying you the best this Pujo. The shoes too would not go unnoticed. Dare you show your heels and mismatch your Dhakai saree with red velvet shoes or don’t have a Kolhapuri mojri to accessorize your Dhuti Panjabi and see how the world drags you to your feet! Also, be sure to watch a few mobile PC Chandra versions walk up and down the aisle and pujo stage. As a kid, I wondered why women dressed up in sheets of gold, jewelry that looked like Raavan’s collection to me. With age, I have learnt that the catch here is not to be demoralized by the bullion market. It is also not about what you flash but when you procured it. How much of what you own is heirloom and how much of it has been acquired recently. Nouveau riche or ancestral wealth determines your genre again. A typical bong compliment could be: “ Natun gorali? Bah besh” ( Is that a new one? Wow nice) and the aside remark to follow can be as “conclusive” as “Kichhui chilona agey; shobi ekhon goracche.” (Had nothing before, see she is getting them now) Ahem! The complexities of what’s right and what is not, is debatable.

look at your clothes…yes, the saree and goyna cannot find a better exhibition than the puja mandap. Commissioned designer exclusives to Gariahat morer stalls, copies of Sabyasachi and Satya Paul to online carbon prints, displaying your wardrobe over five glorious days is the heart of Bong Durga Pujo. There can be nothing as traumatic as discovering the lady standing beside you at pushanpanjali wearing a saree similar to yours. Did I say traumatic? Read catastrophic! The dokaandaar who promised you “ektai piece didi” is dead and so is dear hubby who spent some few hundred dollars buying you the best this Pujo. The shoes too would not go unnoticed. Dare you show your heels and mismatch your Dhakai saree with red velvet shoes or don’t have a Kolhapuri mojri to accessorize your Dhuti Panjabi and see how the world drags you to your feet! Also, be sure to watch a few mobile PC Chandra versions walk up and down the aisle and pujo stage. As a kid, I wondered why women dressed up in sheets of gold, jewelry that looked like Raavan’s collection to me. With age, I have learnt that the catch here is not to be demoralized by the bullion market. It is also not about what you flash but when you procured it. How much of what you own is heirloom and how much of it has been acquired recently. Nouveau riche or ancestral wealth determines your genre again. A typical bong compliment could be: “ Natun gorali? Bah besh” ( Is that a new one? Wow nice) and the aside remark to follow can be as “conclusive” as “Kichhui chilona agey; shobi ekhon goracche.” (Had nothing before, see she is getting them now) Ahem! The complexities of what’s right and what is not, is debatable.

look at your clothes…yes, the saree and goyna cannot find a better exhibition than the puja mandap. Commissioned designer exclusives to Gariahat morer stalls, copies of Sabyasachi and Satya Paul to online carbon prints, displaying your wardrobe over five glorious days is the heart of Bong Durga Pujo. There can be nothing as traumatic as discovering the lady standing beside you at pushanpanjali wearing a saree similar to yours. Did I say traumatic? Read catastrophic! The dokaandaar who promised you “ektai piece didi” is dead and so is dear hubby who spent some few hundred dollars buying you the best this Pujo. The shoes too would not go unnoticed. Dare you show your heels and mismatch your Dhakai saree with red velvet shoes or don’t have a Kolhapuri mojri to accessorize your Dhuti Panjabi and see how the world drags you to your feet! Also, be sure to watch a few mobile PC Chandra versions walk up and down the aisle and pujo stage. As a kid, I wondered why women dressed up in sheets of gold, jewelry that looked like Raavan’s collection to me. With age, I have learnt that the catch here is not to be demoralized by the bullion market. It is also not about what you flash but when you procured it. How much of what you own is heirloom and how much of it has been acquired recently. Nouveau riche or ancestral wealth determines your genre again. A typical bong compliment could be: “ Natun gorali? Bah besh” ( Is that a new one? Wow nice) and the aside remark to follow can be as “conclusive” as “Kichhui chilona agey; shobi ekhon goracche.” (Had nothing before, see she is getting them now) Ahem! The complexities of what’s right and what is not, is debatable.

look at your clothes…yes, the saree and goyna cannot find a better exhibition than the puja mandap. Commissioned designer exclusives to Gariahat morer stalls, copies of Sabyasachi and Satya Paul to online carbon prints, displaying your wardrobe over five glorious days is the heart of Bong Durga Pujo. There can be nothing as traumatic as discovering the lady standing beside you at pushanpanjali wearing a saree similar to yours. Did I say traumatic? Read catastrophic! The dokaandaar who promised you “ektai piece didi” is dead and so is dear hubby who spent some few hundred dollars buying you the best this Pujo. The shoes too would not go unnoticed. Dare you show your heels and mismatch your Dhakai saree with red velvet shoes or don’t have a Kolhapuri mojri to accessorize your Dhuti Panjabi and see how the world drags you to your feet! Also, be sure to watch a few mobile PC Chandra versions walk up and down the aisle and pujo stage. As a kid, I wondered why women dressed up in sheets of gold, jewelry that looked like Raavan’s collection to me. With age, I have learnt that the catch here is not to be demoralized by the bullion market. It is also not about what you flash but when you procured it. How much of what you own is heirloom and how much of it has been acquired recently. Nouveau riche or ancestral wealth determines your genre again. A typical bong compliment could be: “ Natun gorali? Bah besh” ( Is that a new one? Wow nice) and the aside remark to follow can be as “conclusive” as “Kichhui chilona agey; shobi ekhon goracche.” (Had nothing before, see she is getting them now) Ahem! The complexities of what’s right and what is not, is debatable.

Of course, we are not a bitchy tribe. We are fantastic intelligent people, almost always bestowed with good looks or some talent, be it painting, singing, writing, acting, dancing, photography or simply dressing up. And one could find ample demonstrations of each in the Pujo Mondop. We do it well and we do it with all our competence. In other words, we are competent and we are competitive. The only flipside is, sometimes, everyone is clamoring for a space on the stage and there are few cheerleaders and audience on the ground: Bathroom singers, gawky dancers, school sketchbook artists, birthday card writers and everyone with a DSLR camera or with a husband who has a DSLR which is one and the same thing in this instance. Having said all that, pujo is what tugs at the heart of all Bongs everywhere in the world, no matter whether it is a “ghoroa” pujo in Johannesburg or the full on “dhoomdhaam” at Singapore or London or the weekend get together in Bay Area. It is about community bonding, and all things Bong, food, adda, music, dance, dressing up, and if PNPC is such an integral part of the BONG DNA, so be it!!

We do not even spare our gods. I just heard someone say, “Maayer mukutta ektu byenka. Kartik ki ektu tyera naaki re? Uff Lokkhir sareeta ki gyeyo. Sarashwatir hashita bhari mishti. Ar oshur ke dekh, puro tamil movier hero…” ( Isn’t ma durga’s crown a bit tilted? Kartik looks cock eyed, Lakshmi's saree is so behenji type and Saraswati has a cute smile. Asur looks like a hero from a Tamil film…”) Till the next one! Dugga Dugga!! Ashche bocchor abar hobe!

The article was first published in my regular column Shuddh Shakahari Desi on Bkhush.com

Sunday, November 1, 2015

Traveler's note

City lights, skyline and silhouettes

Breath of a perfume,

An euphoria of losing, finding and locking a lost map

Fingers discovering contours like a voyager on a conquest.

Whispering winds, lyrical rains, and a moist inviting earth.

Nothing changes.

Just the coordinates, just another country.

Breath of a perfume,

An euphoria of losing, finding and locking a lost map

Fingers discovering contours like a voyager on a conquest.

Whispering winds, lyrical rains, and a moist inviting earth.

Nothing changes.

Just the coordinates, just another country.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)